by Alec Wilkinson

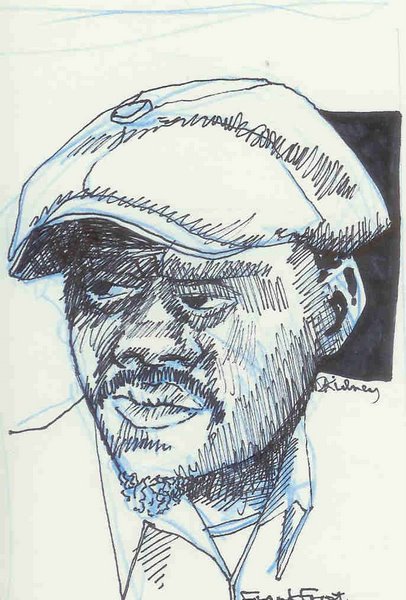

I can’t write briefly about Ry Cooder, the virtuoso guitarist who has a new record, “Pull Up Some Dust and Sit Down.” Admiration for his accomplishments, his singularity, and the longevity and diversity of his career intervene. For more than forty years, since Cooder released his first record, “Ry Cooder,” in 1970, he has been a musician other musicians have followed closely, and no popular musician has a broader or deeper catalog. He has played songs so simple that they are hardly songs, and songs so complex that they would tax, if not overwhelm, the capacities of most lauded guitarists. He had quit making rock ‘n’ roll records sixteen years before Rolling Stone, in 2003, named him the 8th greatest guitarist on their list of the 100 Greatest Guitarists of All Time (three of the seven ahead of him are dead guys). Even so, his influence has been felt more than his records have been heard, with perhaps one exception: the group of elderly Cuban musicians whom he assembled and recorded in 1997 and called the Buena Vista Social Club.

Cooder’s guitar playing is expressive, elegant, and rhythmically intricate. It frequently has a pressured attack that he has described as having the feel of “some kind of steam device gone out of control.” His sense of phrasing was partly imprinted in his childhood by a record of brass music made by a group of African-American men who found instruments in a field left by Civil War soldiers during a retreat, and played them according to their own inclinations. If you wonder what his sensibility sounds like when applied to rock ‘n’ roll—one version of it anyway—the most widely known example I can think of comes from the period when Cooder had been hired to augment the Rolling Stones during the recording of “Let It Bleed.” He was playing by himself in the studio, goofing around with some changes, when Mick Jagger danced over and said, How do you do that? You tune the E string down to D, place your fingers there, and pull them off quickly, that’s very good. Keith, perhaps you should see this. And before long, the Rolling Stones were collecting royalties for “Honky Tonk Women,” which sounds precisely like a Ry Cooder song and absolutely nothing like any other song ever produced by the Rolling Stones in more than forty years. According to Richards in his recent autobiography, Cooder showed him the open G tuning which became his mainstay and accounts for the full-bodied chordal declarations that characterize songs such as “Gimme Shelter,” “Jumpin’ Jack Flash,” “Start Me Up,” and “Brown Sugar.” The most succinct way I can think of to describe the latticed style that Keith Richards says he has sought to achieve with Ron Wood is to say that for thirty-five years the Stones have been trying to do with four hands what Cooder can do with two.

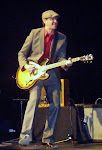

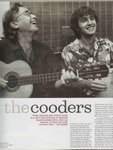

Cooder might have been heard more widely except that he doesn’t like to perform. He doesn’t care for being watched so closely or having to entertain. “I couldn’t go out there anymore and say, ‘Ladies and gentlemen, and especially you ladies,’” he says. The people who like the applause should have it, he feels, but he says he doesn’t care for it. After performing, he used to feel like a withered balloon under a chair on the day after a child’s birthday party. He grew up in recording studios and is more at home there, privately trying to capture something ephemeral and elusive—“the big note,” a friend of his has said, the one that makes all the other concerns fall away. In the last few years, he has toured briefly in Europe and Japan and Australia, with his son, Joachim, playing drums and Nick Lowe playing bass—but not in North America.

For most of Cooder’s career he arranged songs from other writers and various historical sources ranging from Depression era songs, to Bix Beiderbecke’s repertoire, to folk and drifter and cowboy songs, miner’s songs, work songs, surf songs, jukebox songs, calypsos, roadhouse and dance hall songs, protest songs, and songs from the registry of rhythm and blues—but in 2003 he began recording albums of his own material. (My own introductory list of highlights from Cooder’s earlier period: “Great Dreams from Heaven,” “How Can you Keep on Movin’,” “Get Rhythm,” which has a fantastic video, “In a Mist,” “Ditty Wah Ditty,” “Smack Dab in the Middle,” “Tattler,” “France Chance,” “Little Sister,” “Dark at the End of the Street,” “Maria Elena,” “I Think It’s Going to Work Out Fine,” “The Very Thing That Makes You Rich,” and I’ll stop, but I could keep going happily.) The recent records formed a kind of Los Angeles trilogy. The first, “Chavez Ravine.” was inspired by black-and-white photographs of the hill town community inhabited by Mexicans and destroyed to build Dodgers Stadium. The second, “My Name is Buddy,” concerned a red cat named Buddy and his adventures during the most virulent period of anti-workingman and anti-communist feeling. One of the songs he sings is “Red Cat Till I Die.” The third record, “I, Flathead,” is a desert narrative about salt-flat drag racers and an alien racer entangled in a complicated moral dilemma.

What “Pull Up Some Dust and Sit Down” shares with them is an indignation over the economic and ethical disparities of American life and the destructive and scoundrely meanness of the privileges given to the rich. “No Banker Left Behind,” ridicules the considerations extended to the prosperous men and women who grabbed everything not nailed down during the last few years. The norteño “El Corrido de Jesse James,” a lampoon of the notion of honor among thieves, has Jesse James, sitting around in heaven, wishing to have his forty-four returned in order to persuade the bankers to “put that bonus money back where it belongs.” In the sleek country rocker “Quicksand,” a Mexican man describes a border crossing during which the guide for his group leaves in the middle of the night, and the man who takes over dies the next day in the sun. “Then a Dodge Ram truck drove down on us / Said I’m your Arizona vigilante man / I’m here to say, You ain’t welcome in Yuma / I’m takin’ you out as hard as I can.”

“Dirty Chateau” is an exchange between a man with a big house and inconsiderate habits and his maid whose people were farm workers. In the reggae shaded “Humpty Dumpty World,” God deplores the insubstantiality of his creation, with its rabble-rousing politicians and craven television commentators. “I thought I had built upon a solid rock / but it’s just a Humpty Dumpty World,” he sings.

“Baby Joined the Army” is a haunting, mesmeric lament by a young man whose simple girlfriend signs up to become a solider. She’s tired of her town and was lured by the assurance that “If I get killed in battle, I still get paid.”

In the trancy moan, “Lord Tell Me Why” a baffled, older working man wonders why, “A white man ain’t worth nothing in this world no more.” And “John Lee Hooker for President” is a hallucinated description by John Lee Hooker of his Presidency, where all the Supreme Court Justices are “fine looking women,” and mealy-mouthed corruption is not tolerated. “I don’t care if you’re Republican or Democratic / Under John Lee Hooker everything’s going to be copastatic”

“I Want My Crown,” sounds cousin-like to some of Cooder’s earlier recordings, among them “Billy the Kid,” and “Money Honey” from “Into the Purple Valley,” released in 1972, in which unlikely ensembles of stringed instruments were invoked more or less the way horn parts usually are. “Republicans changed the lock on the heavenly door / keys to the kingdom don’t fit no more,” and “If there’s a god / I think he’s got to bottle up and go,” Cooder sings. In the twitchy guitar and mandolin crossfire, you can hear a kind of wild and snaky joy, a rarefied strut that seems to be the song’s throbbing heart.

August 30, 2011

Read more http://www.newyorker.com/online/blogs/newsdesk/2011/08/ry-cooder-pull-up-some-dust-and-sit-down.html#ixzz1kPPJFL2c

Tuesday, January 24, 2012

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

.jpg)

.jpg)

No comments:

Post a Comment