Thursday, July 26, 2012

Ry Cooder’s Rabble-Rousing New Album (from The New Yorker)

Originally posted July 25, 2012 by Alec Wilkinson

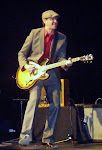

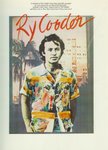

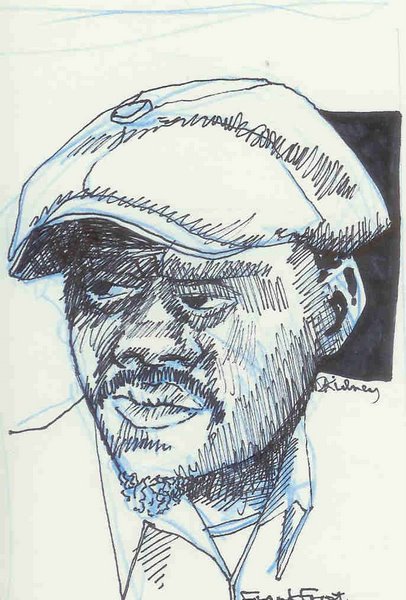

Ry Cooder, who over the course of fifty years has become one of the most singular musicians in America, has a new record, “Election Special,” a collection of songs with a political cast, which comes out in August. Cooder is nothing like as well known as he might be, because he would rather do practically anything than perform in public. He established himself initially as a studio musician, playing in private, and in the past decade he has played in public only a handful of times, several of them only as a sideman. “The people who like the applause should have it,” he once said, “I just don’t care for it.” He has appeared so infrequently that a feeling of nervousness has built up around the occasion. What he will meet, he knows, is three rows of guitar players with their camera phones aimed at his hands, and three more rows of wiseasses, saying, “This is supposed to be a great guitar player? How come he’s not shredding?” Remarks like that can go a long way to dampen the pleasure of the occasion for him, especially if the theatre is intimate.

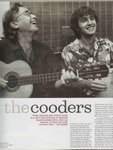

As for his abilities, no other guitar player has mastered the range of styles that Cooder has, or even come close—variations of blues playing (Robert Johnson and Big Bill Broonzy come to mind); slide playing that is sometimes so succinct it is searing; Joseph Spence-style fingerpicking; his own version of electric guitar playing, the most widely known example of which is “Honky Tonk Women,” which Keith Richards based on Cooder’s playing (Cooder was recording with the Stones at the time, on “Let It Bleed,” and Richards wrote the song after listening to him). Cooder’s reach is wide—if you don’t believe me, search Ry Cooder and see all the musicians who list him as an influence. Paul Simon once asked a guitar maker to build him a guitar like Cooder’s—it’s the guitar Simon is holding on the cover of “You’re the One.”

Guitar playing is not the only thing Cooder does, though. He also assembled, rehearsed, picked the repertoire for, and recorded a group of old men in Cuba whom he called The Buena Vista Social Club. The record he made with them was the best-selling in world-music history, and led many musicians and producers to see dollar signs when they looked at Cuba. Cooder’s uncommonness as an artist is the exemplification of Rainer Maria Rilke’s remarks, originally made about Cezanne, “The further one goes, the more private, the more personal, the more singular an experience becomes, and the thing one is making is, finally, the necessary, irrepressible, and, as nearly as possible, definitive utterance of this singularity.”

The songs that Cooder has chosen to record, and his own writings, too, have always had a populist tendency. He likes unions. He likes working men and their lore, detectives, and shadowy parts of Los Angeles, where he has lived all his life. “Election Special” expresses his scorn and outrage about what used to be called current events. “Some of these tunes are a little bitter, I will admit,” he has said. The “Mutt Romney Blues” is sung as if by Romney’s dog, the one he tied on the roof of the car when his family went on vacation. “It don’t look right / don’t seem right,” the dog sings. “Hot in the day / cold all night; Where I’m goin’ I just don’t know / Po’ dog got to bottle up and go.”

“The Wall Street Part of Town,” has a narrator looking for refuge in the part of town where the wind always blows at your back and the ground tilts in your favor. In “Cold Cold Feeling,” Obama is wandering alone, late at night: “I walked up and down the White House / Till I wore the leather out from under my shoes / I didn’t have nothing but the cold cold President blues.” The narrator in “Going to Tampa” is on his way to the convention with ideas in his head. Bring back Willie Horton and scare the nation and blame the Mexicans is one of them.

The record rises to a climax with “Take Your Hands Off It,” Cooder’s rebuke to politicians and their posses, the harm they have caused in the service of greed, and the damage they have done to essential rights around the world. “Get your dirty hands off my Constitution,” it begins, and each verse is a reprimand that spreads like the circles from a stone tossed into a pond. “Get your greasy hands off my Bill of Rights,” and so on, through reproductive rights and war-making. “You don’t speak for God, you know he don’t belong to you.” Pete Seeger believes that songs are more effective as political tools than writing is, because a piece of writing is read once, and songs are sung over and over. A firebrand song is what “Take Your Hands off It” is, a rabble-rousing call, and by the end, you feel all stirred up and ready to close the curtain behind you and pull some levers.

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

.jpg)

.jpg)

No comments:

Post a Comment